Peter Malipa1, Innocent Lanjesi2, Richard Abuduo3, Macdonald Gondwe4, Towera Maureen Maleta5 Linda Mipando6, Clophat Wonder Baleti7

- Ministry of Health, Mangochi District Health Office, Nursing and Midwifery Officer

- Ministry of Health, Mangochi DHO, Dental Surgeon

- Ministry of Health, Mangochi DHO, Senior Clinical Officer

- Ministry of Health, Mangochi DHO, Senior Nursing and Midwifery Officer

- Kamuzu University of Health Sciences-Towera Maureen Maleta

- Kamuzu University of Health Sciences- Linda Mipando

- Ministry of Health, Mangochi DHO, Clinical Officer

Introduction

Birth preparedness (BP) entails a detailed plan that surrounds the delivery of the child. It includes immediate identification of negative signs and symptoms that require prompt management, a plan of delivery place and midwife, emergency requirements like money, transport schedule, and a significant other who can decide in case of unforeseen obstetric complications1. BP is made by the health care facilities, health care professionals, and the pregnant woman, her significant others, and society at large. It is a specified action plan and decision made that covers the antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum period of the woman. This plan aids pregnant women in accessing skilled services during labor and consequently attends promptly to any identified complications. If birth preparedness is planned appropriately, it contributes significantly to the reduction of maternal and neonatal mortality as the pregnant women and their families are adequately prepared for the birth or any arising complications1.

Lack of birth preparedness will lead to poor maternal health2 . The unprepared family wastes time in getting organized, finding money, recognizing the complications, reaching the appropriate referral facility, and finding transport3. Pregnant women and their families need to have adequate knowledge of birth preparedness to enable them to respond appropriately to complications that may arise because informed women will be in a better position to make reasonable and on-time decisions4.

Poor maternal health leading to maternal morbidity and mortality is a major problem in Africa5. The situation is more serious for women in Sub-Saharan Africa, where one in every 16 women dies because of pregnancy-related causes. In fact, Sub-Saharan Africa accounts for 98% of maternal deaths6. More than three-fourths of maternal deaths could be averted if all women had access to skilled care, which is considered the cornerstone and key intervention to minimize complications associated with pregnancy and childbirth7. However, lack of transportation and concern over the cost of services, particularly inadequate preparation for rapid action in the event of obstetric complications, are factors contributing to delays in receiving skilled obstetric care2. Pregnancy-related complications, both for the mother and the newborn, could be largely alleviated if there is a well-consolidated BP plan developed during pregnancy and implemented at the time of delivery8. The World Health Organisation (WHO) indicates that birth preparedness and complication readiness (BPCR) reduces home delivery with a consequent increase in skilled attendance during labor and childbirth7.

Review of delivery records at Mangochi District Health Office in Malawi has shown that more than 50% of women seeking skilled attendance during delivery report very late due to a lack of birth preparedness. Some come in the advanced active phase of labour or the second stage of labour, while others come having already delivered at home or on the way in the absence of midwives. Consequently, such women may be prone to infections, postpartum hemorrhage, obstetric fistula, and even death, while the neonates may be prone to numerous neonatal infections, including birth asphyxia9, which may lead to some serious complications and death. A number of factors determine women’s knowledge on birth preparedness. A community-based survey from Ethiopia10 found that educational status, age, religion, family income, and knowledge of obstetric danger signs were significantly associated with birth preparedness and complication readiness.Therefore, this study sought to investigate knowledge and determinants of birth preparedness among pregnant women attending antenatal care services in the district of Mangochi, Malawi.

Method And Materials

Research Design

This was a facility-based descriptive cross-sectional study that used both quantitative and qualitative approaches. A cross-sectional study design allowed measurements to be taken at one specific point in time, and no follow-up of participants was performed. A cross-sectional study ensured that the phenomenon under study was captured at that point in time11. This allowed the researcher to assess the predictors of birth preparedness in Mangochi. On the other hand, the quantitative approach enabled the researcher to make inferences about significant predictors of birth preparedness. A qualitative approach was used to have an in-depth understanding of birth preparedness from the respondents’ perspective.

Setting

The study was conducted in Mangochi district, Malawi. According to the Malawi National Statistical Office (NSO), the estimated population of Mangochi was 1,148,611. The district has 56 health facilities, with most of them being government-owned. Most of the Mangochi population are farmers who rely on subsistence crop production, though a small population engages in fishing. The languages spoken are Yao and Chichewa, which are dominant. The district has a literacy rate of 53 percent. The main religions in the district are either Islam or Christianity, whereas the predominant ethnic groups are Yao and Chewa12.

Specifically, the study took place in the following public health facilities: Mangochi District Hospital, Makanjira Health Centre, Monkey Bay Community Hospital, Namwera Health Centre, and Chilipa Health Centre. A multistage sampling technique was used to select health facilities for the study. Primarily, all health facilities in the district were stratified into five existing zones as demarcated by the Mangochi District Health Office. The stratum was also based on the geographical location of the facilities within the district. Then, in each zone, all facilities were written on a piece of paper, folded, and placed in a box. The researchers then shook the box and randomly selected one facility in each zone, thus coming up with one health facility in each zone to be a representative in the study. The above randomly selected facilities were ideal because they have a high flow of antenatal care attendance. Except for Mangochi District Hospital, the rest of the selected facilities are located in rural areas.

Study period

Data was collected from September to November 2022.

Study Population

Study participants were pregnant women of any gestational age and gravidity who came to attended antenatal care during the study period.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria:Every pregnant woman who was willing and consented to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria:pregnant women who presented with danger signs or were unable to communicate, and those not willing to be interviewed.

Sample Size determination

The total sample size was 384 using the Cochran formula. This sample size was calculated at a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error (degree of accuracy) of ±5%. The study used the power of 80 percent. A total of 382 participants responded to the study, representing a 99.5% response rate. Two respondents voluntarily withdrew from the study. Participants were interviewed using the questionnaire. Qualitatively, five focus group discussions were conducted. One focus group discussion composed of ten purposively selected participants was conducted at each study facility.

Sampling technique.

A simple random sampling technique was used for quantitative data collection, while purposive sampling was used for qualitative data collection. The researchers identified the pregnant mothers attending the antenatal care clinic in the study area who were willing to participate in the study. The researchers cut small pieces of paper on which were separately written yes or no. These were folded and placed in a small carton, and then study participants were asked to pick a paper from the box once without putting it back. Those who picked papers with a yes were allowed to participate in the quantitative data collection. This was done daily until the required sample was reached.

Data collection instrument and method

Quantitative data were collected using a structured questionnaire adapted and modified from Johns Hopkins Program for International Education in Gynecology and Obstetrics (JHPIEGO): Maternal and Neonatal Health on monitoring birth preparedness and complication readiness. The adapted

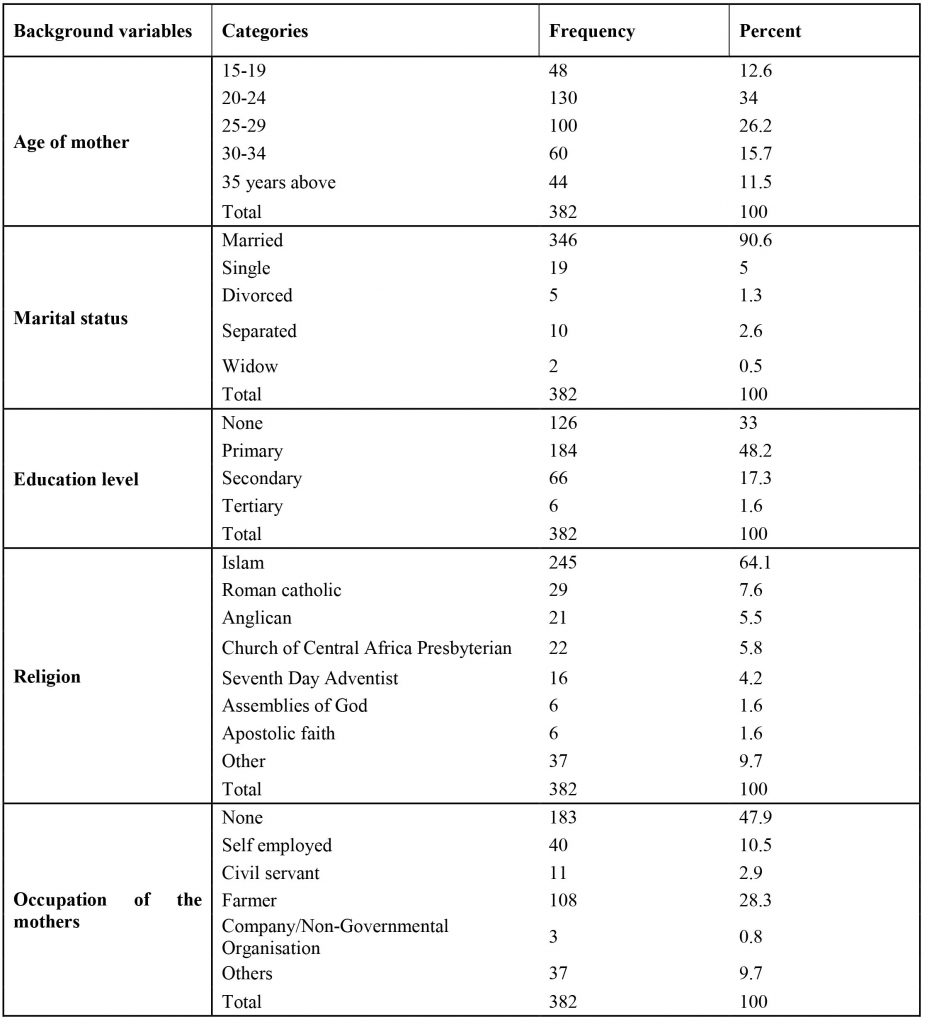

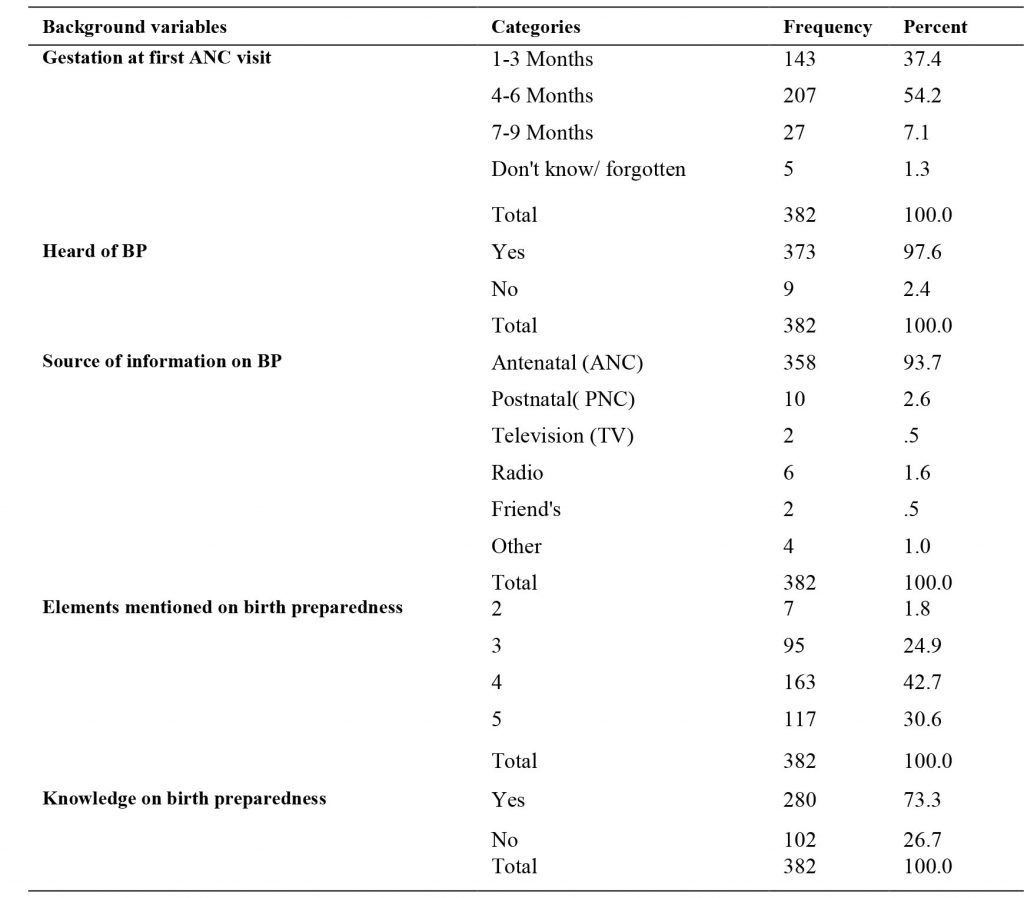

Among the total study participants, (54.2% n=207) had started antenatal care at 4-6 months of gestational age, while (37.4 %, n=143) of the women started antenatal care at a gestational age of 1-3 months. In addition, (7.1%, n=27) women had started antenatal care at 7-9 months of gestation, while (1.3%, n=5) said they did not know. Many women (97.6%, n=373) responded that they had heard about birth preparedness (BP), while (2.4%, n=9) of respondents said they had never heard about birth preparedness.

Source of information about birth preparedness

A high proportion of the respondents got information on birth preparedness from the antenatal clinic (93.7%, n=358) seconded by the postnatal clinic, which was at (2.6%, n=10). The majority of the respondents (73.3%,n=280) had adequate knowledge of birth preparedness as they were able to mention at least four elements of birth preparedness (place of delivery, transport, blood donor, resources, birth companion) as shown in Table 2.

At the 0.05 level of significance using Spearman’s rho, a significant association has been shown between birth preparedness and maternal education, religion, husband occupation, and maternal occupation as shown in Table 3. All the above predictors had a very weak effect size.

Table 3. Birth preparedness and bivariate analysis results

| Variable | Correlation coefficient | Sig (2-tailed) |

| Religion | -0.127 | 0.013 |

| Maternal education | -0.122 | 0.017 |

| Mother’s occupation | 0.103 | 0.044 |

| Husband occupation | 0.18 | 0.000 |

The study also used focus group discussions to collect qualitative data. This study revealed the following three major themes, namely: knowledge on birth preparedness and danger signs, attitude of the health care workers, mainly nurses/midwives, and communication barriers to health talk.

Knowledge on birth preparedness and danger signs

The majority of the mothers had knowledge on birth preparedness and were able to mention at least four elements in birth preparedness, like resources (money, cloth,plastic sheet, torch or candle, and basin), place of delivery, transport, blood donor, birth companion, among others. One mother expressed in this way: ‘During antenatal clinics we are told to keep items like money, basins, plastic sheet, torch, or candles for delivery. In addition, we are advised to identify a blood donor and who to accompany us to the hospital during delivery (Participant 006), Namwera Health Centre. On danger signs in mother and neonate, the majority of the mothers were able to mention danger signs in mother and neonate, like convulsions, fever, vaginal bleeding, and inability to breastfeed. One mother responded as follows: “The common danger signs I know are convulsions, PV bleeding, edema, fever, and inability to breastfeed, and we are taught to go to the hospital when we see this”(Participant 004, Chilipa Health Centre).

Attitude of the health care workers

The mothers also mentioned the health facility as the place of delivery. However, in response to the attitude of the health workers (nurses/midwives), the majority of the mothers expressed dissatisfaction with the attitude of nurses/ midwives. Many said that most of the nurses were rude, while others said the health workers were judgmental. One mother expressed the issue like: ‘ We are sometimes called names up to the extent of being asked like” Was I there when you were doing sex with your spouse?” (Participant 010, Monkey Bay Community Hospital).

Some participants expressed that the attitude of some other health workers was good, thus helping them to be more attentive during health education. One mother from Makanjira added:

“Like during my previous antenatal visit, the nurse who was giving us health education was so cheerful and humorous. All those who attended the talk were very eager to grasp what the nurse was teaching us. The topic was about birth preparedness and danger signs in mothers and neonates” (Participant 008, Makanjira Health Centre).

Communication barriers to health services.

Respondents said communication was the main barrier when accessing the health service. They said many of the health workers could not speak or understand the Yao language, which is the main language of the study area. One woman said this: ‘Communication is a challenge. Most nurses and doctors will speak either Chichewa or English to us. We can’t understand what they want to communicate. Even when they are giving a health talk, they teach us in Chichewa. Our local language is Yao. This communication breakdown acts as a barrier”(Participant 007, Mangochi District Hospital).

Another participant added: “Most of the time, health care workers give health talks in an open space. This makes our concentration low as there are a lot of distractions.” (Participant 002, Chilipa Health Centre)

Discussion

This facility-based study has attempted to assess knowledge on birth preparedness among pregnant mothers in Mangochi District, South-east Malawi. The study findings have shown that 73.3% of the respondents had knowledge on birth preparedness. The main source of information on birth preparedness was the antenatal clinic (93.7 %, n=358). The results are similar to the study carried out in central Ethiopia13, which found that 76.8 % of the participants had knowledge on birth preparedness.

The age groups of the respondents were unevenly distributed, with the age group of 20-24 years more dominant. This is probably because this reproductive age group is sexually active. This is in contrast to a study done in Uganda14 in which they found that the age groups of the respondents in a similar study were evenly distributed.

In terms of the education level, most of the respondents (48.2% n=184) ended at the primary level of education. Three-quarters of the study area being a rural setting, the level of girl child education may still be low, coupled with early marriage, which is rampant9. In the current study, knowledge on birth preparedness was seen to be higher among the educated respondents, especially those who attained secondary and tertiary levels of education, than those who did not attend any formal education and those who ended in primary education. This corresponds to the findings of a study conducted in Uganda2, which found that knowledge of BPACR was higher among the educated than the uneducated. This could be because an educated person can easily understand health-related issues. On religion, the majority of the respondents were Muslims (64.1%), as the predominant people in the area are Muslims, hence representing a greater percentage in antenatal care attendance in the study. In relation to the occupation of the respondents, almost half of the respondents (47.9%) were unemployed. This could be due to low levels of education attained by most of the respondents. Unemployment is one of the key factors that affects health care services in Malawi. Economic constraint due to unemployment as cited by15, is one of the barriers to access to health care services in Malawi.

Regarding the gestational age of the first antenatal visit with the current pregnancy, about half of the respondents (54.2%, n=207) started antenatal care in the second trimester because most of them were staying far away from the hospital. This concurs with what a study done in Bahir Dar Zuria Woreda, North-West Ethiopia, found that mothers who lived within short distances from the health facility were more likely to initiate ANC visits early than those who travelled more than one hour16 . Attending antenatal care is very significant because most of the pieces of information about pregnancy and childbirth birth for example, about BPACR, are given during antenatal care services10.

The study also revealed that components of BP were being taught during antenatal care clinics, as 93.7% of the mothers responded that they were educated on BP at ANC clinics. This is consistent with findings of a similar study conducted in Ibadan, Ethiopia1. Advising pregnant mothers on BPCR during antenatal care contact is vital to keep the course of the pregnancy safer and prepare the women to deliver at health facilities17.

In this study, the factors associated with BP on bivariate analysis were: maternal level of education, maternal occupation, occupation of the husband, and religion. The level of education was statistically associated with birth preparedness on bivariate analysis, as revealed in this study. Those who had a tertiary education had more knowledge on birth preparedness as compared to those with primary level and below. Similarities to this finding were seen in studies carried out in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania6 , which revealed that education is a predictor of birth preparedness and complication readiness. The ability of educated women to make decisions on issues concerning their health can explain this phenomenon. More educated mothers tend to have better awareness of the warning signs of obstetric complications12. It might also be related to the fact that educated women have a better power to make their own decisions in matters related to their health and the expected expenses. The results indicated that the level of education influenced the ability and the quality of decisions on birth preparedness and complication readiness. Women with a higher level of education are able to make better decisions on birth preparedness. Therefore, the education of women should be encouraged in the communities. The occupation status was also associated with birth preparedness and complication readiness on bivariate analysis. The occupation is the most probable steady source of income for an individual. In this study, women who were employed by the government and those whose husbands were employed were more likely to prepare for birth and complications than those with no employment. Similar findings were reported in another study in Ethiopia10.

Similar to studies in the Sub-Saharan region18 our findings confirm that provider attitudes influence maternal health-seeking behavior. The study has found that some of the health workers had a bad attitude towards the pregnant mother. A bad attitude towards pregnant mothers may lead to some women shunning away from attending antenatal care, resulting in poor knowledge on birth preparedness. However, this is dissimilar to the findings of the study conducted in North West, Ethiopia19, which showed that patients and clients had relative satisfaction with the quality of nurses’ work, perceptions of people about their attitudes and behaviors.

Summary

Generally, the study has found the existence of adequate knowledge on birth preparedness among pregnant women in Mangochi District, Malawi. Socio-demographic characteristics of religion, maternal education, maternal occupation, and husband occupation were factors associated with birth preparedness. These findings highlight the need for targeted health education campaigns focusing on women with limited formal education. Such a strategy would assist pregnant mothers to identify danger signs during antenatal, labour, and delivery, and prepare for obstetric complications and therefore seek emergency obstetric care on time to minimize maternal and neonatal mortalities. Further research is needed to explore the role of male partner involvement in birth preparedness in rural settings.

Limitation of the Study

This study attempted to reduce selection bias by giving all eligible pregnant women in the study facilities an equal chance to be participate. One limitation is the use of self-reported data, which may be subject to recall bias. However, the large sample size enhances the reliability of our findings.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest was declared by the researchers.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the CHEER project for the financial support towards the study. We also thank Dr. Mwakikunga and Prof. Lampiao for the technical/scientific support. Lastly, the study participants cannot go unmentioned for the role they played in the study.

References

1. Adeteye DE, Ndikom CM, Akinwaare MO, Dosunmu TO. Factors Influencing Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness among Post-Natal Women in Selected Primary Health Centers in Ibadan, Nigeria. European Journal of Medical and Health Sciences. 2023;5(4):63–7.

2. Feyisa Balcha W, Mulat Awoke A, Tagele A, Geremew E, Giza T, Aragaw B, et al. Practice of Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness and Its Associated Factors:A Health Facility-Based Cross-Sectional Study Design. INQUIRY. 2024 Jan;61:00469580241236016.

3. Berhe AK, Muche AA, Fekadu GA, Kassa GM. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women in Ethiopia: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Reprod Health. 2018 Dec;15(1):182.

4. Lemma T. Knowledge about obstetric danger signs and associated factors among women attending antenatal care at Felege Meles Health Center, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2018. EC Gynaecol. 2020;9:1–9.

5. Jhpiego. Monitoring birth preparedness and complication readness:tools and indicators for maternal and newborn health.Johns Hopkins University/Center for Communication Programs, the Center for Development and Population Activities and the program for Appropriate Technology in Health. 2004;

6. Mulugeta AK, Giru BW, Berhanu B, Demelew TM. Knowledge about birth preparedness and complication readiness and associated factors among primigravida women in Addis Ababa governmental health facilities, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2015. Reprod Health. 2020 Dec;17(1):15.

7. World Health Organization. World Health Organization. Strategies towards Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality. 2015;

8. Tunçalp Ӧ., Were WM, MacLennan C, Oladapo OT, Gülmezoglu AM, Bahl R, et al. Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns—the WHO vision. Bjog. 2015;122(8):1045.

9. Mgawadere F, Unkels R, Kazembe A, Van Den Broek N. Factors associated with maternal mortality in Malawi: application of the three delays model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017 Dec;17(1):219.

10. Ananche TA, Wodajo LT. Birth preparedness complication readiness and determinants among pregnant women: a community-based survey from Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020 Dec;20(1):631.

11. Zangirolami-Raimundo J, de Oliveira Echeimberg J, Leone C. Research methodology topics: Cross-sectional studies. Journal of Human Growth and Development. 2018;28(3):356–60.

12. National Statistical office. Malawi Population and Housing Census Main Report-2018. 2019;

13. Girma D, Waleligne A, Dejene H. Birth preparedness and complication readiness practice and associated factors among pregnant women in Central Ethiopia, 2021: A cross-sectional study. Plos one. 2022;17(10):e0276496.

14. Florence M, Atuhaire C, Nkfusai CN, Shirinde J, Cumber SN. Knowledge and practice of birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in Openzinzi Hciii, Adjumani District, Uganda. Pan African Medical Journal [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 May 21];34(1). Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/pamj/article/view/209125

15. Sakala D, Kumwenda MK, Conserve DF, Ebenso B, Choko AT. Socio-cultural and economic barriers, and facilitators influencing men’s involvement in antenatal care including HIV testing: a qualitative study from urban Blantyre, Malawi. BMC Public Health. 2021 Dec;21(1):60.

16. Alemu Y, Aragaw A. Early initiations of first antenatal care visit and associated factor among mothers who gave birth in the last six months preceding birth in Bahir Dar Zuria Woreda North West Ethiopia. Reprod Health. 2018 Dec;15(1):203.

17. Safer WHOD of MP, Organization WH. Counselling for maternal and newborn health care: A handbook for building skills [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2010 [cited 2025 May 21]. Available from: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=KSjcMlLQaOgC&oi=fnd&pg=PP2&dq=17.%09Safer+WHODoMP,+World+Health+Organization.+Counseling+for+Maternal+and+Newborn+Health+Care:+A+Handbook+for+Building+Skills.+World+Health+Organization%3B+2010.&ots=-9wtUW18-e&sig=8AQCigIWLzXIgGFpBfUbcoLA0Q4

18. Jonas K, Crutzen R, Van Den Borne B, Reddy P. Healthcare workers’ behaviors and personal determinants associated with providing adequate sexual and reproductive healthcare services in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017 Dec;17(1):86.

19. Debelie TZ, Abdo AA, Anteneh KT, Limenih MA, Asaye MM, Lake Aynalem G, et al. Birth preparedness and complication readiness practice and associated factors among pregnant women in Northwest Ethiopia: 2018. Plos one. 2021;16(4):e0249083.