Charles Bijjah Nkhata1,2, Alexander J. Stockdale2,4, Memory N. Mvula1,2, Milton M. Kalongonda1, Martha Masamba1,3, Isaac Thom Shawa 1,5 *

- Kamuzu University of Health Sciences, Private Bag 360, Blantyre3, Malawi

- Malawi-Liverpool Wellcome Programme, Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Blantyre Malawi

- Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department, P.O. Box 95, Blantyre Malawi

- Institute of Infection, Veterinary and Ecological Sciences, University of Liverpool, United Kingdom

- University of Derby, Department of Biomedical and Forensic Sciences, Kedleston Road, DE22 1GB, United Kingdom

*Corresponding Author: Prof. Isaac Thom Shawa; Email: i.shawa@derby.ac.uk

Abstract

Background

Viral Hepatitis is a serious public health concern globally with an estimated 1.3 million deaths annually due to hepatitis B and C viruses. Prevention of mother to child transmission is a critical step toward elimination of hepatitis B and C. The main aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of HBV and HCV among pregnant women at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Blantyre.

Method

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted among consecutive pregnant women attending routine antenatal care, and/or admitted at QECH in last quarter of 2021. Of the 114 pregnant women, 84 women consented to participate. Serum was tested for HBsAg and Anti-HCV markers using rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) and compared to Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA).

Results

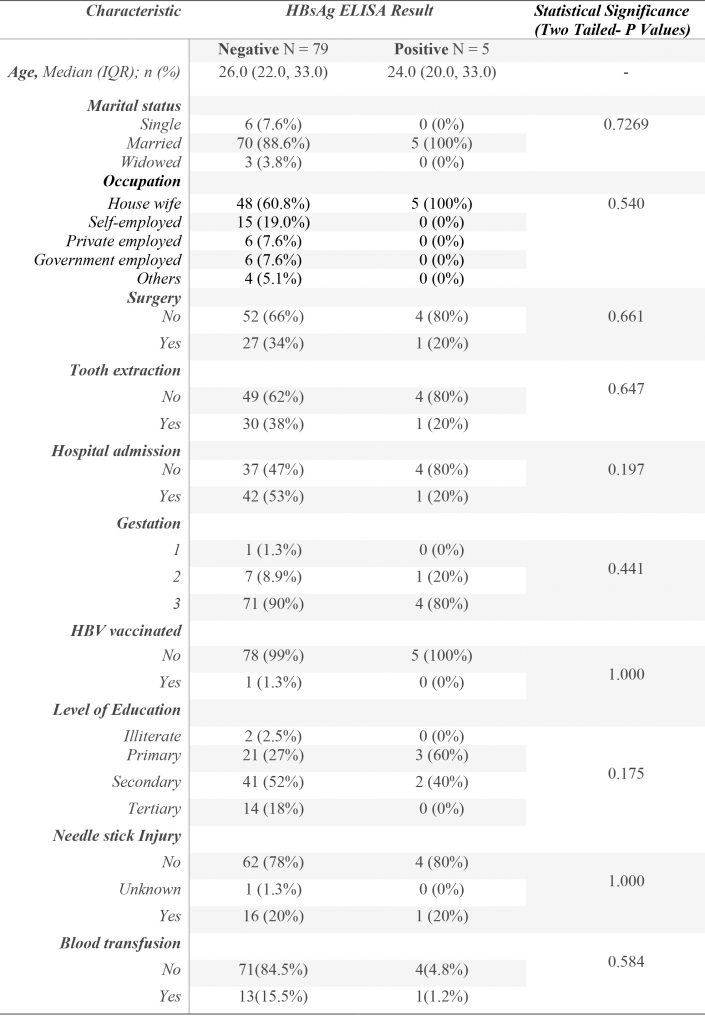

Of the 84 consenting pregnant women, the median age was 25.0 years (IQR: 21.0, 33.0). Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) was detected in 6.0% (n=5/84, 95% CI: 0.03–6.4) of participants using ELISA and in 1.2% (0.2-6.4; n=1/84), using RDTs, while none tested positive for anti-HCV antibodies. There were no significant associations between HBV infection and any of the socio-demographic characteristics or assessed risk factors.

Conclusion

The prevalence of HBV (6%) and HCV (0%) in this population was lower than reported in previous studies of the general Malawian population, where HBV seroprevalence was estimated at 8.1% and HCV below 1%. We highlight potential underdiagnosis using RDTs for HBV, an ongoing significant rate of HBV infection, and a very low prevalence of HCV. Accessible screening and treatment for all positive pregnant women remains essential to eliminate vertical transmission.

Key words: Viral hepatitis, Pentavalent, Triple-test, Pregnant women, Hepatitis B vaccine

Introduction

The burden of chronic hepatitis B and C viruses (HBV/HCV) is disproportionately high in Sub-Saharan Africa where 5.8% of the population is chronically infected with HBV (64.7 million) followed by HCV 0.7% (7.8 million) 1,2. For HBV in Africa, vertical and horizontal transmission during early life predominate, although horizontal transmission in adulthood such as through sexual activity also contributes to the infection rates; whereas HCV infection is most strongly associated with injecting drug use 2. From a systematic review of data covering1990-2018, HBV seroprevalence was estimated at 8.1% among the Malawian general population whereas HCV was below 1% 1. Lipid interactions play a crucial role in HCV susceptibility and resistance to infection, influencing viral entry and replication within host cells 3.

HBV is mainly transmitted at birth from infected mothers and during early childhood; and acquisition early in life is associated with the development of chronic infection. In contrast, when HBV is contracted during adulthood, 5-10% of adults develop persistent chronic HBV infections 4–6; whereas 80% of acute HCV infected individuals progress to chronic hepatitis; with a small proportion (15 – 20%) resolving spontaneously 7–12. In Malawi, nearly 10% of infants born to mothers co-infected with HBV and HIV tested HBV-DNA positive by 48 weeks of age 13.

There is no cure for HBV. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommended infant vaccination against HBV, which was developed in 1989 14,15 and introduced in 2002 into Malawi’s Expanded Programme on Immunisation (EPI), as part of efforts to prevent HBV 16. The HBV birth dose coverage in the African region is estimated at only 18%, followed by a further 2-3 doses in infancy (typically 6, 10, 14 weeks) 17. There is a need for updated and comprehensive data on the epidemiology of viral hepatitis in pregnancy in Malawi. Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to assess the prevalence and associated factors of HBV and HCV among pregnant women at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH) in Blantyre, Malawi.

Methods

This cross-sectional study involved pregnant women attending antenatal care and those admitted to Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH) antenatal Ward in Blantyre, Malawi in 2021. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee (COMREC-U.05/21/3319). The study recruited 84 pregnant mothers receiving maternity and antenatal services over a four-week period (October to November 2021). A convenience sampling technique was used to recruit pregnant women from 18 years and above. Pregnant women with clinical history of epilepsy and severe preeclampsia were excluded from the study. Socio-demographic information, and risk factors for HBV and HCV infection were collected using a semi-structured questionnaire. 5 mL of blood was collected where serum was separated and tested immediately using rapid HBsAg, and anti-HCV assays. Serum samples were tested for HBsAg, and Anti-HCV antibodies using rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs; SD Bioline, South Korea), with all HBsAg results further confirmed using Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA; Bio-Rad, France), which has a reported sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 99.94% respectively. All HBsAg positive samples were retested employing the same protocol and tested in duplicate, in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. ELISA was used as the reference standard for comparison with RDT performance. Statistical analysis was conducted using R version 4.2.1, including Chi-square tests for associations between categorical variables and t-tests for comparisons of continuous variables. Quality control for the RDTs was performed using in-house positive and negative controls with each batch, and tests were conducted by trained personnel under standard laboratory conditions. ELISA assays were carried out in duplicate, incorporating manufacturer-supplied controls on each plate. All positive RDT samples were confirmed by ELISA to ensure accuracy.

Results

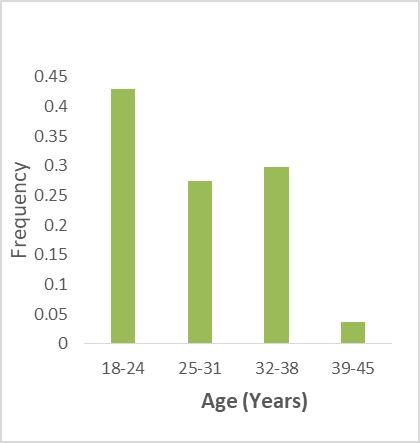

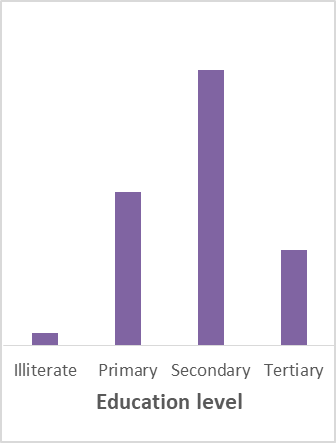

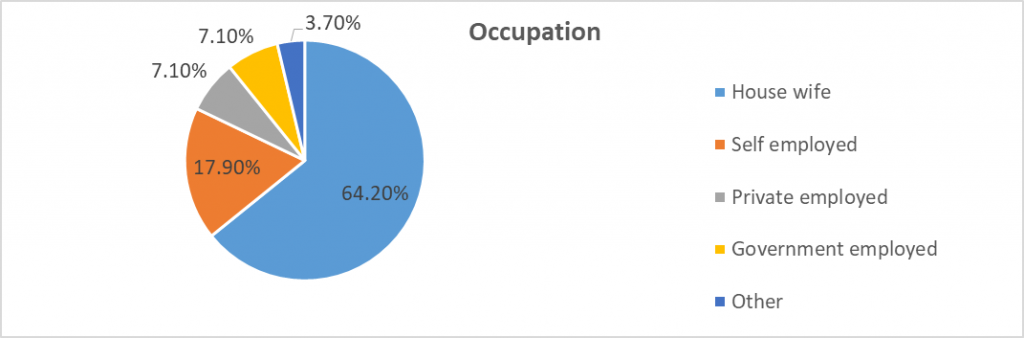

Of the 84 participants (summarized in table 1), the median age was 25 years (IQR:20-33). The prevalence of HBsAg was 6% (5/84; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.03 – 6.4) using the ELISA whereas anti-HCV prevalence was 0.0% (0/84; 95% CI: 0.0 – 4.3), based solely on rapid diagnostic tests. One sample (1/84) tested positive using the rapid diagnostic test. Subsequently, five samples (6%), were retested in duplicate to confirm HBsAg positivity and were all confirmed positive by ELISA. In accordance with the study protocol, as adopted from the manufacturer’s guidelines, all positive samples were retested in duplicate. The sample that tested positive by rapid diagnostic test was also confirmed positive by ELISA.

Table 1. Participant characteristics, stratified by Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Enzyme Linked Immuno-Sorbent Assay (HBsAg ELISA) test results

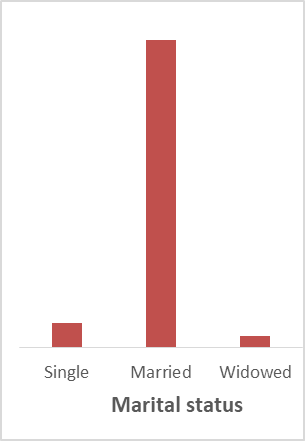

Figure 1. Participant social-demographic characteristics

Discussion

This study provides important insights into the prevalence of HBV and HCV among pregnant women at QECH in Blantyre, Malawi. The observed HBV prevalence of 6.0% aligns with previous studies conducted in Malawi, including a systematic review estimating a prevalence of 8.1% in the general population 1, and a large community survey in Blantyre reporting a 5% prevalence among adults 18,19. Similarly, a community-based study in Karonga found an age-standardised HBV seroprevalence of 4.1%, with a higher prevalence in men (5.3%) compared to women (3.4%) 20. Additionally, HBV prevalence was also reported at 8.6% and HCV at 0% among inmates at Chichiri prison in Blantyre 21. A decade ago, another study reported a 3.5% HBV prevalence among inmates at the same prison 22. The absence of HCV infection in this study is consistent with findings from larger studies in Malawi, which reported HCV seroprevalence of less than 1% among women 23–25; while a large community prevalence survey in Blantyre showed HCV prevalence of 0.2% 18. This low HCV prevalence aligns with regional data suggesting lower endemicity of HCV in sub-Saharan Africa compared to other global regions 26. In this study, HCV screening was conducted solely using rapid diagnostic tests due to limited laboratory resources and unavailability of ELISA for anti-HCV detection. While RDTs offer rapid and convenient screening, they generally have lower sensitivity and specificity compared to ELISA or molecular assays. Consequently, the absence of HCV-positive cases may partly reflect the limitations of the testing method rather than true absence of infection. Future studies should consider incorporating more sensitive diagnostic approaches to accurately determine HCV prevalence in this population.

The HBV prevalence observed in this study is consistent with findings from systematic reviews and meta-analyses among pregnant women in Africa, which reported pooled HBV prevalence rates ranging from 5.89% to 6.8% 27,28. These findings support the classification of Malawi as having intermediate HBV endemicity (2–7%) 29. However, the absence of HCV detection aligns with the lower prevalence estimates observed in sub-Saharan Africa. Together, these results highlight the regional variability in HBV prevalence and suggest the need for targeted interventions in this population.

The lack of significant associations between HBV seroprevalence and socio-demographic or behavioral risk factors in this study may be due to limited sample size, or it may reflect a true absence of such associations in this population. It is also plausible that HBV transmission in this population primarily occurs through vertical or early childhood exposure, consistent with transmission patterns in sub-Saharan Africa 30. Anaedobe et al. conducted a study among pregnant women in Southwestern Nigeria and reported that risk factors including higher parity, lower educational level, and multiple sexual partners were associated with HBV infection 31. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to better evaluate these associations.

The discrepancy between HBV detection using ELISA (6.0%) and RDTs (1.2%) is noteworthy and cannot be attributed to differences in sensitivity alone. In addition to the inherently lower sensitivity of RDTs, factors such as personnel competency, variations in testing environments, and differing levels of quality assurance between the settings in which the tests were performed may have contributed to this disparity. This difference is particularly concerning in low-resource settings where RDTs are commonly used. Employing more sensitive diagnostic tools, such as ELISA, is crucial for accurate HBV detection, especially in antenatal care programs where missed diagnoses could hinder efforts to prevent MTCT.

The WHO emphasizes routine HBV testing for pregnant women as part of the triple elimination strategy for HBV, syphilis, and HIV. This recommendation underscores the significant public health impact of HBV and the availability of effective interventions, such as tenofovir antiviral therapy and timely HBV vaccination beginning at birth, to prevent vertical transmission. Currently, Malawi continues to implement the WHO guideline to triple-test for HBV, HIV, and syphilis in antenatal care and ensures that all women who test positive for HBsAg receive Tenofovir/Lamivudine. However, the limited availability of resources hinders the HBV testing in some hospitals which negatively impact smooth functioning of healthcare services in the obstetrics and gynaecology departments.

In Malawi, infants born to mothers who are HBV-negative receive a three-dose pentavalent vaccine, which includes Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis, Hepatitis B, and Haemophilus influenzae type B (DTP-HepB-Hib), with doses given at 6, 10, and 14 weeks. In contrast, infants born to HBV-positive mothers receive a birth dose of HBV immunoglobulin within the first 24 hours of life, and 4 doses of hepatitis B vaccine at 1 month, 6, 10, and 14 weeks. These protocols are part of the national antenatal care, and Malawi HIV treatment guidelines and are currently being implemented in Malawi. Continued execution of HBV immunization and testing programmes will likely lead to a reduction in the prevalence of HBV.

Conclusion

The current findings indicated a 6.0% seroprevalence of HBV infection among pregnant women at QECH which calls for strengthened antenatal care programs, including universal HBV screening, to prevent MTCT of HBV. Given the absence of HCV detection, continued surveillance is needed to monitor its prevalence in this population. These efforts are crucial in the global endeavour to eliminate chronic viral hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030. While the study provides useful preliminary data, the relatively small sample size and the single-centre design may limit the generalisability of the findings and the ability to detect associations with socio-demographic or behavioural factors. Larger, multi-site studies are recommended to validate these findings.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all study participants for their involvement. Special thanks to Mr Kelvin Katundu and Mr Niza Silungwe for their valuable support during this study, and to Professor Luis Gadama for his support during data collection.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the first, and corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are conflict of interest related to this study.

References

1. Stockdale AJ, Mitambo C, Everett D, Geretti AM, Gordon MA. Epidemiology of hepatitis B, C and D in Malawi: systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):1-10. doi:10.1186/s12879-018-3428-7

2. World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report 2024: action for access in low- and middle-income countries. WHO. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240091672. Published April 9, 2024. Accessed December 15, 2024.

3. Shawa IT, Sheridan DA, Felmlee DJ, Cramp ME. Lipid interactions influence hepatitis C virus susceptibility and resistance to infection. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2017;10(1):17-20. doi:10.1002/cld.643

4. Liaw YF. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. In: Thomas HC;, Lok ASF, eds. Viral Hepatitis: Fourth Edition. 4th ed. Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: Wiley (Publisher); 2013:143-153. doi:10.1002/9781118637272.ch10

5. Villeneuve JP. The natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2005;34:S139-S142. doi:10.1016/S1386-6532(05)80024-1

6. Yang HC, Kao JH. Revisiting the Natural History of Chronic HBV Infection. Curr Hepatol Rep. 2016;15(3):141-149. doi:10.1007/s11901-016-0304-z

7. Knapp S, Warshow U, Ho KMA, et al. A polymorphism in IL28B distinguishes exposed, uninfected individuals from spontaneous resolvers of HCV infection. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(1):320-325, 325.e1-2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.005

8. Rauch A, Gaudieri S, Thio C, Bochud PY. Host genetic determinants of spontaneous hepatitis C clearance. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10:1819-1837. doi:10.2217/pgs.09.121

9. Thomas DL, Thio CL, Martin MP, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2009;461(7265):798-801. doi:10.1038/nature08463

10. Grebely J, Raffa JD, Lai C, Krajden M, Conway B, Tyndall MW. Factors associated with spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus among illicit drug users. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2007;21(7):447-451.

11. Gerlach JT, Diepolder HM, Zachoval R, et al. Acute hepatitis C: High rate of both spontaneous and treatment-induced viral clearance. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(1):80-88. doi:10.1016/S0016-5085(03)00668-1

12. Shawa IT, Felmlee DJ, Hegazy D, Sheridan DA, Cramp ME. Exploration of potential mechanisms of HCV resistance in exposed uninfected intravenous drug users. J Viral Hepat. 2017;0(0):1-7. doi:10.1111/jvh.12720

13. Chasela CS, Kourtis AP, Wall P, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection among HIV-infected pregnant women in Malawi and transmission to infants. J Hepatol. 2014;60(3):508-514. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2013.10.029

14. Pattyn J, Hendrickx G, Vorsters A, Van Damme P. Hepatitis B Vaccines. J Infect Dis. 2021;224(Supplement_4):S343-S351. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa668

15. Stasi C, Silvestri C, Voller F. Hepatitis B vaccination and immunotherapies: an update. Clin Exp Vaccine Res. 2020;9(1):1. doi:10.7774/cevr.2020.9.1.1

16. Chipetah F, Chirambo A, Billiat E, Shawa IT. Hepatitis B virus seroprevalence among Malawian medical students: A cross-sectional study. Malawi Medical Journal. 2017;29(1):29-31. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/mmj.v29i1.6

17. Stockdale AJ, Meiring JE, Shawa IT, et al. Hepatitis B Vaccination Impact and the Unmet Need for Antiviral Treatment in Blantyre, Malawi. J Infect Dis. 2022;226(5):871-880. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiab562

18. Stockdale A, Meiring J, Shawa IT, et al. Evaluation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) epidemiology, vaccine impact and treatment eligibility: a census-based community serological survey in Blantyre, Malawi. J Hepatol. 2020. doi:10.1016/s0168-8278(20)32027-4

19. Stockdale AJ, Meiring JE, Shawa IT, et al. Hepatitis B Vaccination Impact and the Unmet Need for Antiviral Treatment in Blantyre, Malawi. J Infect Dis. 2021. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiab562

20. Riches N, Njawala T, Thom N, et al. P23 The chiwindi study: results from a community-based hepatitis B serosurvey in Karonga, Malawi. In: Poster Presentations. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and British Society of Gastroenterology; 2023:A57.2-A58. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2023-BSG.96

21. Chimberenga S, Phiri VS, Mgawa A, et al. Unsafe sexual practices prior to incarceration, and early childhood transmission are potential high-risk factors of Hepatitis B and HIV infection among prisoners in Blantyre, Malawi. Microbes and Infectious Diseases. 2024;0(0):0-0. doi:10.21608/mid.2024.308772.2121

22. Chimphambano C, Komolafe IO, Muula AS. Prevalence of HIV, HepBsAg and Hep C antibodies among inmates in Chichiri prison, Blantyre, Malawi. Malawi Medical Journal. 2008;19(3). doi:10.4314/mmj.v19i3.10937

23. Blach S, Zeuzem S, Manns M, et al. Global prevalence and genotype distribution of hepatitis C virus infection in 2015: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2(3):161-176. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30181-9

24. Rao VB, Johari N, du Cros P, Messina J, Ford N, Cooke GS. Hepatitis C seroprevalence and HIV co-infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(7):819-824. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00006-7

25. Fox JM, Newton R, Bedaj M, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus in mothers and their children in Malawi. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2015;20(5):638-642. doi:10.1111/tmi.12465

26. Sonderup MW, Afihene M, Ally R, et al. Hepatitis C in sub-Saharan Africa: the current status and recommendations for achieving elimination by 2030. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2(12):910-919. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30249-2

27. Wondmeneh TG, Mekonnen AT. Epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection among pregnant women in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24(1):921. doi:10.1186/s12879-024-09839-3

28. Bigna JJ, Kenne AM, Hamroun A, et al. Gender development and hepatitis B and C infections among pregnant women in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis Poverty. 2019;8(1):16. doi:10.1186/s40249-019-0526-8

29. Hou J, Liu Z, Gu F. Epidemiology and Prevention of Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Int J Med Sci. 2005:50-57. doi:10.7150/ijms.2.50

30. Veronese P, Dodi I, Esposito S, Indolfi G. Prevention of vertical transmission of hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(26):4182-4193. doi:10.3748/wjg.v27.i26.4182

31. Anaedobe CG, Fowotade A, Omoruyi C, Bakare R. Prevalence, sociodemographic features and risk factors of Hepatitis B virus infection among pregnant women in Southwestern Nigeria. Pan African Medical Journal. 2015;20. doi:10.11604/pamj.2015.20.406.6206